Philosophy, as they say, “was conceived as wedded to death.” Legions of A-list existential thinkers have tried to “dress the wound of mortality” by making sense of the absurdity and fragility of life: Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Camus … a veritable who’s who list of intellectuals have weighed in on the infinite conundrum, and annoyingly haven’t reached a consensus on the meaning of death (or the meaning of life, for that matter).

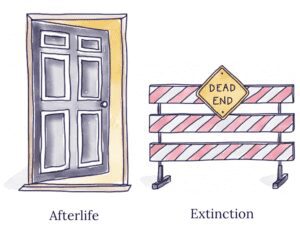

Some philosophers have described death as a rich and verdant afterlife (for which we must prepare, as noted in the religious context), to a total annihilation of the self (poof! Gonzo for good!). These deep thinkers have traditionally regarded death as real (picture a blank wall) or not real (picture a door to another life). There may be some coin flipping involved here to determine what really happens when we flatline.

Some philosophers have described death as a rich and verdant afterlife (for which we must prepare, as noted in the religious context), to a total annihilation of the self (poof! Gonzo for good!). These deep thinkers have traditionally regarded death as real (picture a blank wall) or not real (picture a door to another life). There may be some coin flipping involved here to determine what really happens when we flatline.

In the spirit of waking you up to your little no-way-out-alive pickle (i.e.: YOU ARE DYING SO GET ON WITH THE LIVING!), let’s nibble at the Philosophy Sampler Platter I’ve assembled here for you. Is it an exhaustive list? Hell no. That would have bored me to death to put together and I have better things to do (like watching season two of The White Lotus)! Graze at the notes below and see what resonates for you. Remember … time spent contemplating your inevitable demise counterintuitively leads quality time towards living a life worth living (like I went on and on about here).

Smart musings about your impermanence

Zhuangzi, the ancient 4th century BC Chinese philosopher, pronounced that death was just another ritual to be celebrated—like a going away party for a grand journey to another phase of existence.

Socrates believed that death led to either the blank wall of a dreamless sleep, or the door opening to a passage to yet another life—fear being pointless, regardless of the door that death opened for us. Ever the controversial sort, Socrates professed that death would be a benefit for those who kept their minds sharp.

Plato, Socrates’s reverential student, believed death opened up the door to an ideal world, adding in his two cents here: “I am afraid that other people do not realize that the one aim of those who practice philosophy in the proper manner is to practice for dying and death.” These Ancient Greeks launched the ethos that death provided the liberation of one’s intellectually trained soul from its somatic prison. (Bodies … so banal.)

Epicurus took a cut-and-dried approach to the topic, believing that death was simply the cessation of sensation—therefore inconsequential and of no concern to us, thank you very much. He proclaimed that our fear of death was the one thing holding us back from living lives of fulfillment and that we owed it to ourselves to seek as much sensation as possible, living up our moments while alive, before hitting the proverbial blank wall. (I’d totally have sat beside Epicurus at a dinner party.) (And he’d have gotten me trashed.)

Epicurus took a cut-and-dried approach to the topic, believing that death was simply the cessation of sensation—therefore inconsequential and of no concern to us, thank you very much. He proclaimed that our fear of death was the one thing holding us back from living lives of fulfillment and that we owed it to ourselves to seek as much sensation as possible, living up our moments while alive, before hitting the proverbial blank wall. (I’d totally have sat beside Epicurus at a dinner party.) (And he’d have gotten me trashed.)

The Stoic school of philosophy that emerged in 3rd century Greece argued that without heaven or hell, the time to perfect our virtues and live life to the fullest is today—by meditating on our mortality as a reminder that tomorrow just might not arrive. Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius summed it up well: “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.” Aurelius also notably quipped, perhaps at the first ever open-mic night in ancient history: “Alexander the Great and his mule driver both died and the same thing happened to both.” Ba dum chhh!

Sixteenth century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote extensively about the difference between being melancholic and meditative about death, urging the plain and simple premeditation of death as a way to learn how to die: “To begin depriving death of its greatest advantage over us, let us deprive death of its strangeness, let us frequent it, let us get used to it; let us have nothing more often in mind than death.” High five, Michel.

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer ushered Hindu and Buddhist teachings into Western philosophy in the mid-1800s, espousing a grander view of the universe while considering death, rather than staying mired in the small-minded fears of our individual fates. Schopenhauer had an enduring focus on the contemplation on death in his work, considering death as our destiny fulfilled amidst a “will to live.” When Schopenhauer said, “Without death men would scarcely philosophize,” it was a clear nod to his Grim Reaper muse.

Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish existentialist philosopher, claimed mortality was a defining feature of our existence that could either be disregarded with indifference (not his recommendation) or accepted as a mechanism of transformation to live a life full of passion, deliberate choice, and keen urgency. Modern-day Harvard philosopher Susanna Siegel (I had to find a female voice to join this sausage party) credits Kierkegaard for positioning death “as a horizon that implicitly shapes our consciousness.”

Nietzsche, famous for encouraging us to consummate our lives, proposed the stirring thought experiment of the “eternal return,” asking readers to conceive of having to live their identical lives over and over again, for eternity—every high, every low, every scintillating conversation replayed, every mundane car wash repeated, every bit of tooth-flossing minutia relived. Obvious implications abound: would we want to live this life again? Nietzsche noted that our response to this question would either delight us, change us, or crush us. (You might recall we spoke about this idea here? Oh yes we did.)

19th century American philosopher William James noted that “death is the worm at the core of all our usual springs of delight.” He also poked folks in the ribs with this doozie: “‘Is life worth living? It all depends on the liver.” A big believer in the “life is what you make it” ethos, James encouraged livers to take life by the reins and determine our own realities.

19th century American philosopher William James noted that “death is the worm at the core of all our usual springs of delight.” He also poked folks in the ribs with this doozie: “‘Is life worth living? It all depends on the liver.” A big believer in the “life is what you make it” ethos, James encouraged livers to take life by the reins and determine our own realities.

Martin Heidegger, 20th century German philosopher, espoused that his notion of Dasein—the capacity to conceive of our own death—was essential in the act of being an authentic, existentially-healthy being. Freedom, in all its glory, was to be gained by the acceptance of our death, leading us to a being-towards-death mindset or way of being, squarely rooted in the foresight of the end of it all.

Twentieth century French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre saw death as a reflection of our meaningless existence. No modern-day motivational speaker, his “life has no meaning the moment you lose the illusion of being eternal” line succinctly captures all that we need to say on that matter. Oh but wait! He did say this, too: “Everything has been figured out, except how to live.” That part is kinda motivational.

Perhaps Otto Rank, the first existential therapist, said it best: “some refuse the loan of life to avoid the debt of death.” Let’s all gasp in tandem with that fabulously poetic punch in the nuts.

The livelier philosophies

For every word of self-annihilating insight the philosophical greats have bestowed upon us about death, just as many encouraging sentiments have been churned out about how to make the most of the time we have been allotted. Humans have been concerned with not just making sense of death, but of making sense of life, too—consistently interested in ways to live our years to their fullest.

Roman poet Horace, the dutiful Epicurean, will be forever cherished for his slogan-friendly encouragement to “carpe diem”—i.e.: seize the day—given that there might not be a tomorrow. (It should also be noted that this poem opens with these wise words: “Now is the time to drink!”— so I like Horace already.)

Roman philosopher Seneca graced us 2,000 years ago with words of wisdom on the value of time and the need to live lives as wide as they are long: “The whole future lies in uncertainty: live immediately … life is long if you know how to use it.” Seneca goes so far as to say that we’re essentially dying prematurely by living like we’re destined to be here forever.

17th century Dutch philosopher Spinoza believed that when you’re dead, you’re dead … and preferred to focus on the joys of living rather than meditating on The End. He advocated for the acquisition of self-knowledge as a “free person” ripe with self-esteem. Spinoza clearly bought into Socrates’s notion that the unexamined life wasn’t worth living.

*** *** ***

Guys, this philosophical smorgasbord of death could go on for days, but I need to go make and eat dinner or else I might perish. Who have I missed? Whose voice/ ethos/ way of living have I offended you by not including here? Do tell me. I can be found at jodi@fourthousandmondays.com or over on Instagram these days. What philosophy/ philosophies of life and death influence you? I’m actually asking as a real question, not just a rhetorical “let’s lead an examined life” kind of question. Do tell me!

And in the meantime … don’t not think about your finitude. Don’t not live like you have an expiry date. Let any one of these philosophers make you think. They’d roll over in their graves if they thought you were dismissing their ideas.

P.S.: Did you catch my hint to connect with me on Instagram? Oh, good.

P.P.S.: Oh and just in case you missed it… I’d love you forever if you took 16 minutes out of your life to watch my TEDx talk!